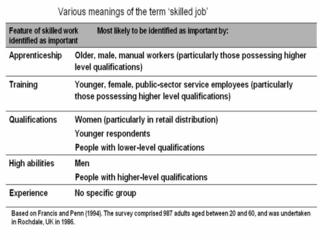

Skill is generally considered to be a possession of the individual. It can take numerous forms-for example, knowledge, dexterity, judgement, linguistic ability-however the assumption is that it accrued by the individual as a product of accumulated education, training and experience. In survey (Francis and Penn, 1994) respondents reported over 16 different definitions when asked the question ‘What do you think is meant by the term skilled job?’. However, there was some convergence around five main characteristics: training, qualifications, apprenticeship, experience and high abilities. Francis and Penn conclude that different occupational groups will categorise skill in different ways, which suggests that person’s conception of skill is largely based on his or her own experiences of employment.

Cockburn (1983: 113) suggests that person, job and setting all three aspects need to be taken into account. In her study of (male) printworkers she argues that:

There is the skill that resides in the man himself, accumulated over time, each new experience adding something to total ability. There is the skill demanded by the job-which may not match the skill in the worker. And there is the political definition of skill: that which a group of workers or a trade union can successfully defend against the challenge of employers and other groups of workers. Cockburn has divided the skills in to three categories because each suggests a different approach to examining skill.

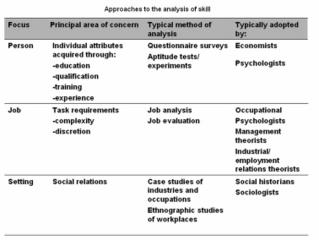

1) Skill in the person: Any analysis that concentrates on the person is likely to attempt to identify individual attributes and qualities, and seek to measure these through, for example, and aptitude test under experimental conditions; typically this approach has been taken by psychologists. Similarly, a questionnaire might be administrated to assess the individual’s education, training and experience, which could then be proxy for skill-a method frequently adopted by economists.

2) skill in the job: If the analytical focus is the job then the concern is less with the person performing the task than with the requirements embedded in the task itself. In this case, attention would be turned towards the complexity of the tasks required to perform the job competently- an approach typically taken by management theorists. It would also include the extent of discretion over the work-an issue of particular interest to industrial/employment relations theorists.

3) skill in the setting: if the focus is on the political and historical setting, an analysis would be assessing the way skill has developed over time and has been ‘constructed’ by different interest groups, rather than being a feature of the person or the job-an approach pursued by some sociologists, but more usually by historians.

These differences in approach to analysing skill are summarised in following table: (Click on diagram to enlarge.)

The approach of Human Capital theorists (Becker, 1964) who argue that in market economy, a person’s human capital will determine their value as an employee. For Human Capital theorist, responsibility for success in work clearly lies with the individual; they invoke the notion of the notion of a meritrocratic society, where individual endeavour is rewarded. There are three problems recognise with the human capital approach:

1) Inequality of opportunity: The approach assumes that everyone has the same opportunity of access to the activities that improve human capital. For example, a person has to be offered a job in order to gain work experience however when there are high rates of unemployment allowing employers to pick and choose, a person with no work experience is less likely to be offered a job, they are consequently unable to gain work experience.

2) Validity of the skill measures: A general problem is whether the variables of education, training and experience are valid measures of skill. The number of years of a person spends in formal education is linked to qualifications attained, but even then it does not necessarily mean that skills learned will be appropriate or transferable to the work setting. Similarly, while the measurement of training may be a better indicator of industry-specific knowledge and aptitude, it does not take into account the applicability of the training to the current context.

3) Use value of the skill: Measurement should include those attributes that have a current value-in other words the measurement of ‘skill in use’ rather than skill possessed. For example, if person learns to speak Nepali and gain qualification proving their competence, does this constitute a skill? If it has some market value, human capital theorists would say yes, but if few employers require Nepali speakers, it value is severely reduced. In other words, skill is not a fixed concept, but it is relative to its market value. In this sense, all knowledge and abilities can be seen as potential skills, but it is the demand for them and their supply that give them value. Therefore, measuring the skills possessed by the person can be misleading without exploring the labour market context.

The approach of assessing skill in the person tends to view skill as an attribute possessed by an individual, and sometimes described as a person’s human capital. While this appears to be a relativity simple way of assessing skill, the problems lie in the methods of measurement and then putting these in to practice.

There is the skill that resides in the man himself, accumulated over time, each new experience adding something to total ability. There is the skill demanded by the job-which may not match the skill in the worker. And there is the political definition of skill: that which a group of workers or a trade union can successfully defend against the challenge of employers and other groups of workers. Cockburn has divided the skills in to three categories because each suggests a different approach to examining skill.

1) Skill in the person: Any analysis that concentrates on the person is likely to attempt to identify individual attributes and qualities, and seek to measure these through, for example, and aptitude test under experimental conditions; typically this approach has been taken by psychologists. Similarly, a questionnaire might be administrated to assess the individual’s education, training and experience, which could then be proxy for skill-a method frequently adopted by economists.

2) skill in the job: If the analytical focus is the job then the concern is less with the person performing the task than with the requirements embedded in the task itself. In this case, attention would be turned towards the complexity of the tasks required to perform the job competently- an approach typically taken by management theorists. It would also include the extent of discretion over the work-an issue of particular interest to industrial/employment relations theorists.

3) skill in the setting: if the focus is on the political and historical setting, an analysis would be assessing the way skill has developed over time and has been ‘constructed’ by different interest groups, rather than being a feature of the person or the job-an approach pursued by some sociologists, but more usually by historians.

These differences in approach to analysing skill are summarised in following table: (Click on diagram to enlarge.)

The approach of Human Capital theorists (Becker, 1964) who argue that in market economy, a person’s human capital will determine their value as an employee. For Human Capital theorist, responsibility for success in work clearly lies with the individual; they invoke the notion of the notion of a meritrocratic society, where individual endeavour is rewarded. There are three problems recognise with the human capital approach:

1) Inequality of opportunity: The approach assumes that everyone has the same opportunity of access to the activities that improve human capital. For example, a person has to be offered a job in order to gain work experience however when there are high rates of unemployment allowing employers to pick and choose, a person with no work experience is less likely to be offered a job, they are consequently unable to gain work experience.

2) Validity of the skill measures: A general problem is whether the variables of education, training and experience are valid measures of skill. The number of years of a person spends in formal education is linked to qualifications attained, but even then it does not necessarily mean that skills learned will be appropriate or transferable to the work setting. Similarly, while the measurement of training may be a better indicator of industry-specific knowledge and aptitude, it does not take into account the applicability of the training to the current context.

3) Use value of the skill: Measurement should include those attributes that have a current value-in other words the measurement of ‘skill in use’ rather than skill possessed. For example, if person learns to speak Nepali and gain qualification proving their competence, does this constitute a skill? If it has some market value, human capital theorists would say yes, but if few employers require Nepali speakers, it value is severely reduced. In other words, skill is not a fixed concept, but it is relative to its market value. In this sense, all knowledge and abilities can be seen as potential skills, but it is the demand for them and their supply that give them value. Therefore, measuring the skills possessed by the person can be misleading without exploring the labour market context.

The approach of assessing skill in the person tends to view skill as an attribute possessed by an individual, and sometimes described as a person’s human capital. While this appears to be a relativity simple way of assessing skill, the problems lie in the methods of measurement and then putting these in to practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment