Human attachments and their loss or disruption represents and important way of trying to understand how early experience can affect later development. Sociability refers to one of three dimensions of temperament (the others being emotionality and activity), which are to be present at birth and inherited (Buss & Plomin, 1984). Specifically, Sociability is:

* Seeking and being especially satisfied by rewards from social interaction.

* Preferring to be with others

* Sharing activities with others

* Being responsive to and seeking responsiveness from others.

According to Kagan et al. (1978), an attachment is: ……an intense emotional relationship that is specific to two people, that endures over time and in which prolonged separation from the partner is accompanied by stress and sorrow.

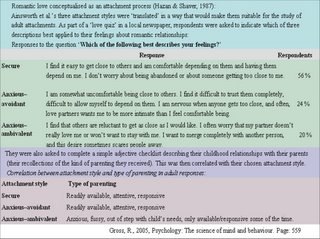

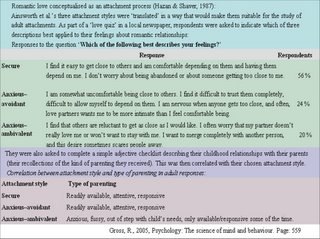

This definition applies to attachment formation at any point in the life cycle, our first attachment acts as a prototype (or model) for all later relationships. According to Hazan & Shaver (1987), attachment theory, as developed by Bowlby and Ainsworth in particular, offers a valuable perspective on adult romantic love, helping to explain both positive emotions (caring, intimacy, and trust) and negative emotions (fear of intimacy, jealousy, and emotional ‘ups and downs’).

Hazan and Shaver were the first to apply Ainsworth et al.’s three basic attachment styles to adult – adult sexual/romantic relationships. Their study tried to answer the question: how are adults’ attachment patterns (in their adult relationships) related to their childhood attachments to their parents.

These results provided encouraging support for an attachment perspective on romantic love. Hazan & Shaver warned against drawing any firm conclusions about continuity between early childhood and adult experience. It would be excessively pessimistic, at least from point of view of the insecurely attached person, if continuity were rule, rather than the exception. The correlations suggest that as we go further into adulthood, continuity with our childhood experiences decreases. The average person participates in several important friendships and love relationships, which provide opportunities for our mental models (Bowlby, 1973, internal working model) of self and others.

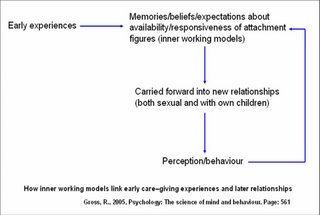

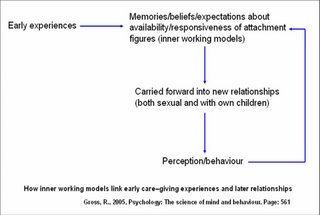

According to Bowbly (1973), expectations about the availability and responsiveness of attachment figure are built in to our inner working models of attachment. These reflect memories and beliefs stemming from our early experiences of care–giving, which carried forward into new relationships, both during childhood and beyond. They plan an active role in guiding perceptions and behaviour.

According to Waldrop & Halverson (1975), boys’ relationships are extensive, while girls’ are intensive. Boys’ friendship groups are larger and more accepting of newcomers than girls’. The level of competition between pairs of male friends is higher than it is between strangers – the opposite of girls. Despite some important gender differences in friendship quality, collaboration and cooperation are most common forms of communication in both boys’ and girls’ friendships.

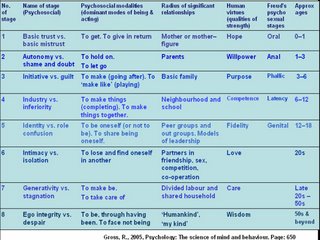

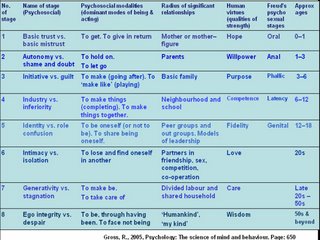

The evaluation of Erickson’s theory defines as follows:

The sequence from identity to intimacy may not accurately reflect present-day realities. In recent years, the trend has been for adults to live together before marrying, so they tend to marry later life than people did in past. Many people struggle with identity issues at the same time as dealing with intimacy issues.

Additionally, some evidence suggests that females achieve intimacy before ‘occupational identity’. The typical life course of women involves passing directly into a stage of intimacy without having achieved personal identity. Sangiuliano (1978) argues that most women submerge their identities into those of their partners, and only mid-life do they emerge from this and search for separate identities and full independence. There’s also a possible interaction between gender and social class. Or example, working-class men see early marriage as a ‘good’ life pattern: early adulthood is a time for ‘settling down’, having family and maintaining a steady job. By contrast, middle-class men and women see early adulthood as a time for exploration, in which different occupations are tried. Marriage tends to occur after this, and ‘setting down’ doesn’t usually take place before 30 (Neugarten, 1975). There’s also evidence of an interaction between gender, race and culture. As Gilligan (1982) has observed: the female comes to know herself as she is known, through relationships with others.

Marriage is an important transition for young adults, because it involves a lasting personal commitment to another person, financial responsibilities and, perhaps, family responsibilities. Marriage and preparation for marriage can be very stressful. Davis (1956) identified mental disorders occurring for the first time in those who engaged to be married. Typically, these were anxiety and depression which began in connection with an event that hinged on wedding date. Since the disorders improved when the engagement was broken off or wedding took place, Davies concluded that it was the decision to make the commitment that was important, rather than the act of getting married itself.

Couples who live together (or cohabit) before marriage are more likely to divorce later, and be less satisfied with their marriages, than those who marry without having cohabited. Also, about 40 percent of couples who cohabit don’t marry. While this suggests that cohabitation may prevent some divorces, cohabits who marry are more likely to divorce.

It’s long been recognised that mortality is affected by marital status. Married people tend to live longer than unmarried people, are happier, healthier and have lower rates of various metal disorders than single, widowed or divorced.

* Seeking and being especially satisfied by rewards from social interaction.

* Preferring to be with others

* Sharing activities with others

* Being responsive to and seeking responsiveness from others.

According to Kagan et al. (1978), an attachment is: ……an intense emotional relationship that is specific to two people, that endures over time and in which prolonged separation from the partner is accompanied by stress and sorrow.

This definition applies to attachment formation at any point in the life cycle, our first attachment acts as a prototype (or model) for all later relationships. According to Hazan & Shaver (1987), attachment theory, as developed by Bowlby and Ainsworth in particular, offers a valuable perspective on adult romantic love, helping to explain both positive emotions (caring, intimacy, and trust) and negative emotions (fear of intimacy, jealousy, and emotional ‘ups and downs’).

Hazan and Shaver were the first to apply Ainsworth et al.’s three basic attachment styles to adult – adult sexual/romantic relationships. Their study tried to answer the question: how are adults’ attachment patterns (in their adult relationships) related to their childhood attachments to their parents.

These results provided encouraging support for an attachment perspective on romantic love. Hazan & Shaver warned against drawing any firm conclusions about continuity between early childhood and adult experience. It would be excessively pessimistic, at least from point of view of the insecurely attached person, if continuity were rule, rather than the exception. The correlations suggest that as we go further into adulthood, continuity with our childhood experiences decreases. The average person participates in several important friendships and love relationships, which provide opportunities for our mental models (Bowlby, 1973, internal working model) of self and others.

According to Bowbly (1973), expectations about the availability and responsiveness of attachment figure are built in to our inner working models of attachment. These reflect memories and beliefs stemming from our early experiences of care–giving, which carried forward into new relationships, both during childhood and beyond. They plan an active role in guiding perceptions and behaviour.

According to Waldrop & Halverson (1975), boys’ relationships are extensive, while girls’ are intensive. Boys’ friendship groups are larger and more accepting of newcomers than girls’. The level of competition between pairs of male friends is higher than it is between strangers – the opposite of girls. Despite some important gender differences in friendship quality, collaboration and cooperation are most common forms of communication in both boys’ and girls’ friendships.

The evaluation of Erickson’s theory defines as follows:

The sequence from identity to intimacy may not accurately reflect present-day realities. In recent years, the trend has been for adults to live together before marrying, so they tend to marry later life than people did in past. Many people struggle with identity issues at the same time as dealing with intimacy issues.

Additionally, some evidence suggests that females achieve intimacy before ‘occupational identity’. The typical life course of women involves passing directly into a stage of intimacy without having achieved personal identity. Sangiuliano (1978) argues that most women submerge their identities into those of their partners, and only mid-life do they emerge from this and search for separate identities and full independence. There’s also a possible interaction between gender and social class. Or example, working-class men see early marriage as a ‘good’ life pattern: early adulthood is a time for ‘settling down’, having family and maintaining a steady job. By contrast, middle-class men and women see early adulthood as a time for exploration, in which different occupations are tried. Marriage tends to occur after this, and ‘setting down’ doesn’t usually take place before 30 (Neugarten, 1975). There’s also evidence of an interaction between gender, race and culture. As Gilligan (1982) has observed: the female comes to know herself as she is known, through relationships with others.

Marriage is an important transition for young adults, because it involves a lasting personal commitment to another person, financial responsibilities and, perhaps, family responsibilities. Marriage and preparation for marriage can be very stressful. Davis (1956) identified mental disorders occurring for the first time in those who engaged to be married. Typically, these were anxiety and depression which began in connection with an event that hinged on wedding date. Since the disorders improved when the engagement was broken off or wedding took place, Davies concluded that it was the decision to make the commitment that was important, rather than the act of getting married itself.

Couples who live together (or cohabit) before marriage are more likely to divorce later, and be less satisfied with their marriages, than those who marry without having cohabited. Also, about 40 percent of couples who cohabit don’t marry. While this suggests that cohabitation may prevent some divorces, cohabits who marry are more likely to divorce.

It’s long been recognised that mortality is affected by marital status. Married people tend to live longer than unmarried people, are happier, healthier and have lower rates of various metal disorders than single, widowed or divorced.

Gross R. (2005), "Psychology The science of mind and behaviour" 5th edition, Hodder Arnold, London NW1 3BH

No comments:

Post a Comment