Knowledge economy discourse is being used in countries like China and India to make a case for permitting multinational companies however Nepalese are losing allure with Nepal’s development:

The media have been all agog over the rise of crises in Nepal. Women, children and other non-combatants are being primary victims. The key characteristics of the war in Nepal at high risk of internal fighting are neither political nor social, but mere economic. Maoist rebel leaders form themselves as heroically fighting to guide in an era of liberty and prosperity. However it seldom works this way. Civil war typically leaves a legacy of economic, social and political ruin. But the damage extends to neighbour countries because drugs and terrorism flourish and spread from regions of disorder, even they appear to be isolated from their country which is happening in India now. Another common consequence of rebellion and disorder is rape, strike and fight.

According to World Bank calculations, the total of 2.3 billion people in China and India, nearly 1.5 billion earn less than $2 a day. Both are poor, largely agricultural countries. Nepal is also poor where around sixty percent people depend in agriculture. China, India and Nepal are sailing in same boat however Nepal didn’t choose its main priorities as unemployment and a spirit of nation’s atma vishwas (self confidence); we can take several such examples a kind of substantial growth seen in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, South Korea in the 1970, China and India today.

Nepal's foreign policy is also good between China and India. There are more influence of India than China because of open border, culture, and climate. Today, India high-tech is not the sole preserve of the rich. Auto rickshaw drivers began using mobile phone so that customers can call for a ride. Technology companies are extending internet connections to the remote locations. Small, renewable electricity generators are appearing in villages, and the government is using home- grown space technology to improve literacy skills and education in far flung areas. This knowledge revolution has begun in our neighbour countries. Conventional wisdom now suggests that globalisation is responsible for this feat. But does Nepal have it as a nation and, if not, what must Nepal do to get it?

Nepal’s illiteracy is reducing only at the rate of 1.3 percent per annum. At this rate, Nepal will need another more or less 50 years to attain a literacy rate of 95 percent. We cannot be industrially and economically advanced and we cannot be technologically advanced unless we are scientifically advanced. One of the critical issues facing Nepal is the gulf between the academic world and industry. Science too has its role to play. The notion that scientific ideas lead to technology and from there to wealth is not widespread. Nepal needs economic liberalisation and competition between Nepali companies which is being tamed, so they are under no pressure to come up with new ideas, nor did academics promote their ideas to industry.

Of course, people are going India, Arab and Developed Countries for employment because of political instability and lack of opportunity for employment and government’s future policy. Some of them are attempting to gain illegal passage to developed countries by holding false passport and documents. Despite the perception that Nepalese immigrants tend to be deprived illiterate prone to crime, Nepalese who emigrates is not that country's most destitute citizens. They tend to come from the mid-skilled classes, not from the poorest. More than anything else, it is a perceived lack of opportunity that encourages citizens to leave country. Government is also encouraging those who are going aboard to train different skills so that their income will increase by many folds, and has already made the first move a program to provide loan through banks to those who cannot afford money to go abroad.

Most of the people in Nepal dream of being overseas so that they are watching foreign channel rather Nepal TV, are also the main source of aspiring to be somewhere else for better future and employment. So many Nepalese dream of leaving significantly threatens Nepal's economic development, social well-being, and political stability. Every year Nepal loses two to three percent of its GNP to brain drain. Nepal loses between 1,000 and 2,000 professors, doctors, and engineers and high skilled professionals annually. This loss means fewer well-educated, ambitious citizens who could help lead our country. However there is an irony here, for if through immigration Nepal loses capital in some forms; gains it through the money its immigrants send back to their families. If we look at the number of households receiving the remittance in Nepal, it increased from 23 percent in 1995/96 to 52 percent in 2003/04, contributed close to about 12 percent to the Nepal’s GDP.

Rich countries like Arab and other Developed countries want migrants' labour, but do not want to look after these newcomers when they grow old. Ideally, rich countries would like a constant rotation of workers, arriving while they are young and active, leaving before they grow old and dependent. For its part, temporary and circular migration is also better for poor country like Nepal. One reason is remittances: the longer an immigrant stays away from home, the smaller the share of his/her wages he/she sends back. In Germany, the same phenomenon happened in reverse. The availability of cheap guest-workers in German factories slowed the adoption of new labour-saving technology. As the saying went at the time: Japan is getting robots while Germany gets Turks.

Nepalese households invest more than half of their savings in physical ones such as land, houses, cattle, and gold instead of putting money into financial assets. In rural areas, the proportion is even higher. This fact shows that Nepalese people mistrust of banks and are the largest consumers of gold. Let us take an example in Pokhara, there have been invested to build houses but they are all empty. Households could earn higher returns by investing in financial assets, and the country would be better off if savings were pooled to finance more productive investments.

This dilemma may help explain why the Nepalese government can seem unsure about security, unemployment, and social stability. There is confrontation between three parties: government, political parties and Communist follower “Maoist”. If we ask about the current situation to them, they give a very simple answer without taking any responsibility that we don’t have a lot of resources like India and China. Now, our greatest resource and valuable export is our human potential. That's a powerful incentive, even if it does spank of actively encouraging a brain drain from developing countries like Nepal. But then, India’s Late Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's well-known prescription still holds: "Better brain drain than brain in the drain". Competition for brains and ideas is where the battle for global influence should be waged.

Above all, Nepal should learn from the experience of other countries to avoid killing incentives for work rather than encouraging people to go abroad, and should make it easier for workers to learn new skills, so it is all the more important to invest in education. All that is needed is a more welcoming environment for foreign educational institutions, investor and students, as well as a greater tolerance for market in tourism. Nepal needs to revitalise its economy, modernise its institutions, rewrite the contract between the members of society and recover its self esteem. I could go on and on, but the point should be clear that Nepal's future is in Nepalese hands and will be what Nepalese make of it.

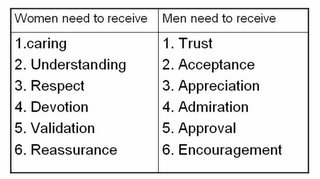

A men’s deepest fear is that he is not good enough or that he is incompetent. He compensates for this fear by focusing on increasing his power and competence. Success, achievement and efficiency are far most in his life. A man appears most uncaring when he is afraid. Just women are afraid of receiving, man are afraid of giving. To extend himself in giving to others means to risk failure, correction, and disapproval. These consequences are most painful because deep inside his unconscious he holds an incorrect belief that he is not good enough. This belief was formed and reinforced in childhood ever time he thought he was expected to do better. When his accomplishments went unnoticed or were unappreciated, deep in his unconscious he began forming the incorrect belief that he was not good enough.

A men’s deepest fear is that he is not good enough or that he is incompetent. He compensates for this fear by focusing on increasing his power and competence. Success, achievement and efficiency are far most in his life. A man appears most uncaring when he is afraid. Just women are afraid of receiving, man are afraid of giving. To extend himself in giving to others means to risk failure, correction, and disapproval. These consequences are most painful because deep inside his unconscious he holds an incorrect belief that he is not good enough. This belief was formed and reinforced in childhood ever time he thought he was expected to do better. When his accomplishments went unnoticed or were unappreciated, deep in his unconscious he began forming the incorrect belief that he was not good enough. The top secret of difference in coping with stress in Men and Women are: When Men become stress, they are increasingly focused and withdrawn. They feel better by solving problems. Men want to make improvements when they feel that they are being approached as a solution to problem rather than as the problem itself. But Women are increasingly overwhelmed and emotionally involved and they feel better by talking about problems.

The top secret of difference in coping with stress in Men and Women are: When Men become stress, they are increasingly focused and withdrawn. They feel better by solving problems. Men want to make improvements when they feel that they are being approached as a solution to problem rather than as the problem itself. But Women are increasingly overwhelmed and emotionally involved and they feel better by talking about problems.  To be honest, when I left Nepal since then I started living alone. This loneliness took me far from everybody and today far from you. I never gave few minutes to think in those six years about the love and caring which you gave me in few days. I instinctively felt a need to talk about my feelings with you. I was not immediately concerned with finding solutions to my problems but rather tried to find relief by expressing myself and being understood. Alas you broke our communication and I came back my lonely world again. I tried to explain you but you didn’t give me any chance.

To be honest, when I left Nepal since then I started living alone. This loneliness took me far from everybody and today far from you. I never gave few minutes to think in those six years about the love and caring which you gave me in few days. I instinctively felt a need to talk about my feelings with you. I was not immediately concerned with finding solutions to my problems but rather tried to find relief by expressing myself and being understood. Alas you broke our communication and I came back my lonely world again. I tried to explain you but you didn’t give me any chance.